Elderly Medicine

Bradford VTS Clinical Resources

- by Dr Sabah Malik

- Last modified: 22nd January 2024

- No Comments

DOWNLOADS

path: ELDERLY MEDICINE

WEBLINKS

- Elderly Medicine super-condensed curriculum –

what you should know (RCGP) - PrescQIPP – prescribing in care homes

FOR PATIENTS

……………………………………..

Information provided on this medical website is intended for educational purposes only and may contain errors or inaccuracies. We do not assume responsibility for any actions taken based on the information presented here. Users are strongly advised to consult reliable medical sources and healthcare professionals for accurate and personalised guidance – especially with protocols, guidelines and doses.

COME AND WORK WITH ME… If you’d like to contribute or enhance this resource, simply send an email to rameshmehay@googlemail.co.uk. We welcome collaboration to improve GP training on the UK’s leading website, Bradford VTS. If you’re interested in a more active role with www.bradfordvts.co.uk (and get your name published), please feel free to reach out. We love hearing from people who want to give.

……………………………………..

Tops Tips

In 1965, Bernard Isaacs coined the term “geriatric giants.” These are common health issues that are found in older people and at time included mobility, balance, problems controlling bladder, and difficulties remembering things. They’ve actually been known since the 1930s. There used to be 5 – which were Falls (now Mobility – because it is more than just Falls), Poor Nutrition, Incontinence, Confusion and Polypharmacy (widened to Medication Problems – because many are simply not taken!).

Today, there are now 9 Geriatric Giants are remembered by the mnemonic MANIC MOLD

- Mobility – including balance problems, sarcopenia and falls – decide what to do if deteriorating – physio? Stop certain meds – like benzodiazepines or antipsychotics if unnecessary (speak with psych?) or trial to reduce opioid medication if pain is okay? Refer to pharmacy team to optimise medicines.

- Elder Abuse – including self-neglect

- Poor Nutrition – including mouth problems, failure to thrive, and the anorexia of ageing. Look at patient’s intake and weight (MUST score if falls).

- Incontinence

- Confusion or impaired Cognition – dementia/delerium. Sometimes “bad behaviour” is because of an infection (Hx, Ex, urine dip, bloods), pain (ask about grimaces, calling out on moving), constipation, or depression. May need to assess for memory and use appropriate memory assessment tool.

- Medication Problems – including polypharmacy – review medications and take off medication that is not needed. Avoid creating polypharmacy.

- Osteoporosis

- Lonliness

- Depression

As a health care professional, review these 9 things in most of your elderly patients because often they won’t volunteer them. Yet once you discover and treat them, they can transform the lives of the elderly. For instance by improving things such as moving around easier, reducing falls, and feeling better mentally. Our duty is to help older people live a better life.

Sarcopenia has been defined as an age related, involuntary loss of skeletal muscle mass and strength. Beginning as early as the 4th decade of life, evidence suggests that skeletal muscle mass and skeletal muscle strength decline at 1% per year from age 40 onwards in a linear fashion.

Therefore, in an 80 year old person there will be a 50% of mass lost compared to when they were 40!!! This can be reversed or even prevented if the elderly are encouraged to remain active and mobile.

Relatives and health professionals often exacerbate sarcopenia by encouraging other family members to do all the things the elderly person once used to do. Okay, perhaps they can’t do a big shop, but there is no reason not to take them out with them or get them do a small shop every day rather than in one big swoop. Moving elderly people with good mobility into a bungalow also reduces their future muscle mass and strength (imagine the number of times of times you go up and down the stairs building your muscles and how that is reduced to zero when you remove those stairs!). Of course, there is always a risk of falls, but falls are more likely in those with weak muscle mass.

Exercise is the only effective strategy shown to alleviate sarcopenia.

Examining the feet of elderly patients is important because they can provide signals for what is truly going on for the patient – which you may not pick up otherwise. For example:

Self neglect – Often, elderly patients can appear immaculate, but the real story is revealed by their feet. Dirty feet and long toenails can indicate poor self care.

Changes in skin condition, temperature, color, or the presence of ulcers can be indicative of underlying medical issues. For instance diabetes and circulatory problems.

Deformity of the feet might indicate arthritis or poor footwear.

For Falls Prevention: Foot problems, such as corns, calluses, and improper footwear, can increase the risk of falls among elderly individuals. Regular foot assessments can help identify and address issues that may contribute to falls.

In summary, looking at the feet of elderly patients is essential for early detection, falls prevention, improved mobility, customized care, and the prevention of complications, all of which contribute to better overall health and well-being in this population.

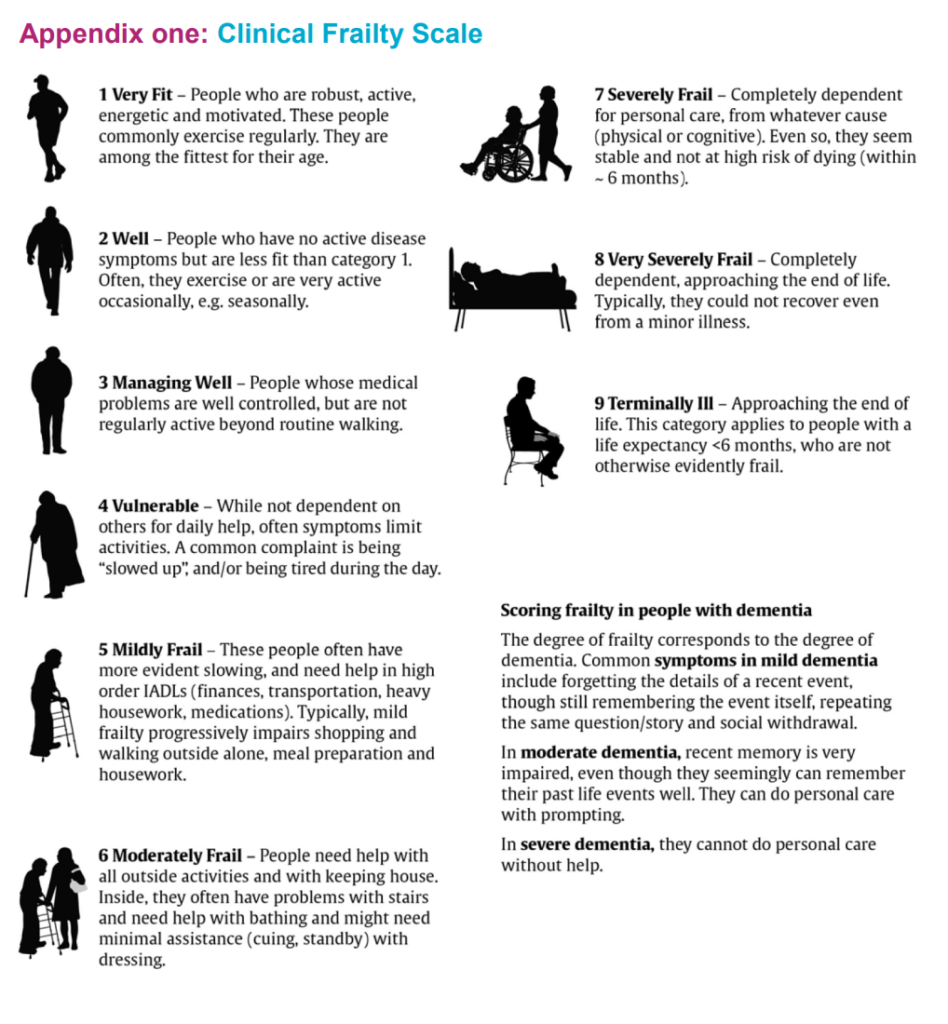

Right now, older people with mild, moderate, or severe frailty often end up in the hospital when things get really bad, but if we find frailty early and plan how to take care of them, we can help them better. This helps reduce the chances of them getting really sick and helps them get better faster if they do. It also slows their decline meaning they have a better quality of life before the ultimate ending to life happens. When you get old what would you prefer in the last 10 years of your life? Option 1 – where you decline gradually over the 10 years, each year worse than the one before, until you die or Option 2 – where you are reasonably well all the way uptil the last year of your life?

You can slow/reverse someone’s frailty.

The five frailty criteria are

- weight loss,

- exhaustion,

- low physical activity,

- slowness and

- weakness.

WELSW

Nursing & Care Homes - what to do

Review notes

When you’re called out for a home visit to a nursing home or care home patient, before you set off to see them, REVIEW THE MEDICAL NOTES.

- Review previous consultations pertaining to the same presenting complaint as what you are visiting for. (Use the search box)

- Check last set of entries – from other GPs, OOH, community nursing

- Discharge summaries/hospital letters

- Are there any Outstanding recalls/CDM/Blood results

- RESPECT FORM AND RESUSCITATION STATUS – are these in place? Do you need to set one up?

Before you get there… think!

- Think of all the differentials

- And the questions you need to ask to hone down the differentials

- And all the possible things that you might have to do

- Don’t think too hard. Just mull things over in your head.

E.g. called out for swollen legs

On my journey…

- Is it one leg or two?

- If one – could be DVT (think D-dimer, Wells Score), bakers cyst, cellulitis (Rx antibiotics – have they got any allergies)

- If both legs – more likely CHF (review chest, make sure not in AF, do ProBNP, may need mild diuretics)

- Try and issue prescriptions when you come back from surgery unless it is super urgent.

- There is less likely a chance that you will make with an electronic prescription compared to a handwritten one.

- Let the patient know you are doing this and when they can go and collect the item.

Most practices print of a Home Visit Summary Sheet for you.

This is to help you with your consultation – in case you need something like

- a list of repeats

- recent bloods

But please log into the Electronic Medical Record (EMR) for a more comprehensive review of the patient – like the last set of consultations. Don’t just rely on the printed sheet.

Please destroy any physical paperwork that has a patients information on it.

- This is your responsibility.

- Do not throw it in a bin.

- Do not leave it in your car.

- Instead, put it through the practice’s shredder (every practice has one).

- It is a serious breach of confidentiality if you leave the home visit patient summary sheet lying around! Destroy it when you are done with it by shredding (tearing it up is NOT enough).

PS Many practices now offer electronic access to patient records securely via you phone – apps like Brigid. Ask your practice! Or research it if they don’t know and help improve your practice (a leadership project perhaps?)

WHEN YOU GET THERE

FIRST – acute problem

- Deal with the acute problem that they have called you out for

- Always look at vitals – P, BP, Temp, Sats

SECOND – the 9 Geriatric Giants

There are now 9 Geriatric Giants are remembered by the mnemonic MANIC MOLD

- Mobility – including balance problems, sarcopenia and falls – decide what to do if deteriorating

-

- Stop certain meds – like benzodiazepines or antipsychotics if unnecessary (speak with psych?)

- Trial to reduce opioid medication if pain is okay?

- Refer to pharmacy team to optimise medicines.

- Physio for sarcopenia (weak muscles)?

-

- Elder Abuse – including self-neglect

-

- Ask the patient on a 1-1 when alone “How are you doing here?”, “How are they treating you here”

- Unusual brusing?

- Look at the feet – often tells you if the patient is being looked after or not!

-

- Poor Nutrition –

-

- Look at the mouth for any oral problems – poor dentures, ulcers (beware oral cancer), thrush

- Look at the rest of body – anorexia of ageing?

- Ask about patient’s oral intake

- Ask for the patient’s weight (MUST score if falling).

-

- Incontinence

-

- Ask if they are incontinent. All the time or some of the time? Any increasing confusion with it?

- Are they drinking enough? (ask about oral intake)

- Is there a strong smell indicating UTI?

- Dipstick urine/Send off for MSSU

-

- Confusion or impaired Cognition

-

- Is it dementia or delerium?

- Dementia – do a memory assessment score.

- Sometimes “bad behaviour” is because of

-

- an infection (Hx, Ex, urine dip, bloods),

- pain (ask about grimaces, calling out on moving),

- constipation, or

- depression.

-

-

- Medication Problems

-

- Review medications and take off medication that is not needed. Ask if patient not taking or refusing any.

- Reduce polypharmacy

- Avoid creating polypharmacy.

-

- Osteoporosis

-

- FRAX score?

- DEXA Scan if appropriate

-

- Lonliness

-

- Ask patient “Often, as people age, they feel more lonely. Are you experiencing that too”? “How bad is it my dear?”

- Discuss with Nursing/Care home what to do. e.g. Any befriending services, encouragement at home/nursing home community events (e.g singing on a Thursday afternoon)

-

- Depression

-

- Ask patient “You seem a bit down to me. Do you find that you are down in your spirits a lot?”

- Antidepressant? Behavioural activation?

-

- Ask if patient has a DoLS in place – ensure this is coded in the notes – add to problem list and summary.

- RESUS STATUS/RESPECT FORM to be considered for all. Use template

- Palliative care register/review if appropriate

END OF LIFE CARE

- If at the end of life, start anticipatories?

- Stop unnecessary meds

- Get Palliative Care involved? Gold Line?

- DNACPR/RESPECT Forms – discuss with patient/relatives and complete.

- Keep care home staff in the loop.

Tell the patient

When you are unwell with any of the following…

- Vomiting or Diarrhoea (unless only minor and mild)

- Fevers, sweats and shaking (unless only minor and mild) – this can often happen with common cold/flu, chest infections, water infections

Then

- STOP taking the medicines I have written down for you

- Restart these when you are well (after 24-48 hours of eating and drinking normally)

- If you are in any doubt, contact the pharmacist, doctor, nurse or call 111.

Also

- Take some rest

- Drink plenty of sugar-free fluids. Aim to drink at least three litres (five pints) a day, UNLESS YOU HAVE HEART FAILURE – in which case ask your Heart Failure nurse or GP or ring 111 (you may need to stick to around 1.5-2 litres). If you have Heart Failure, weigh yourself every day. If you suddenly gain more than 2Kg in 3 days, contact the emergency doctor or call 111.

- Try to keep to your normal meal pattern, but if you are unable to, for any reason, you can replace some or all of your meals with snacks and/or drinks that contain carbohydrate such as yoghurt, milk and other milky drinks, fruit juice or sugary drinks such as Lucozade, ordinary cola or lemonade. You may find it useful to let fizzy drinks go flat to help keep them down

- Avoid too much caffeine as this could make you dehydrated.

- Take painkillers in the recommended doses as necessary.

- Contact your GP to see if treatment with antibiotics is necessary.

- If you are vomiting uncontrollably, contact your GP or call 111

- Keep taking your insulin or diabetes medications even if you are not eating. HOWEVER, stop metformin and blood pressure medication if you are dehydrated.

- Test your blood four or more times a day and night (ie at least eight times in a 24-hour period) and write the results down. If you are not well enough to do this, ask someone to do it for you.

- Test your urine four or more times a day and night (ie at least eight times in a 24-hour period) and write the results down. If you are not well enough to do this, ask someone to do it for you.

- Testing for ketones

- When diabetes is out of control as a result of severe sickness, it can lead to a condition called diabetic ketoacidosis or diabetic coma if you have Type 1 diabetes. The body produces high levels of ketone bodies causing too much acidity in the blood.

- If you have Type 1 diabetes and your blood glucose level is 15 mmol/l or more or you have two per cent or more glucose in your urine, you will also need to test your urine or blood for ketones. They are a sign that your diabetes is seriously out of control. Ketones are especially likely when you are vomiting and can very quickly make you feel even worse. If a ketone test is positive, contact your GP or diabetes care team immediately.

Medicines to STOP on sick days (mnemonic SADMAN)

- SGLT-2 inhibitors: medicine names ending in “flozins” like canagliflozin, empagliflozin, dapagliflozin

- ACE inhibitors: medicine names ending in “pril” like ramipril, lisonopril, enalapril, captopril, perindopril

- Diuretics: e.g. medicine names ending in “ide” like furosemide, bendroflumethiazide, bumetanide

- Metformin (which is a medicine for diabetes)

- ARBs: medicine names ending in “sartan” like losartan, candesartan, valsartan, irbesartan

- NSAIDs: anti-inflammatory pain killers like ibuprofen, diclofenac, naproxen, ketoprofen

BACK AT THE PRACTICE

- Write up your home visit and the reason why you were called

- Tidy up the repeat medication list – reduce polypharmacy.

- Remember to use appropriate clinical templates (e.g. Ardens, S1, EMIS) for all the other stuff you reviewed and looked at (e.g. medication reviews, CDM, bloods)

- Move on recall dates. Keep recalls to a minimum.

- Liaise with community phlebotomy and observation team for follow up bloods if needed.

- Liaise with Community Matrons/Care Coordinators/District Nurses of other issues that need follow up.

DONT FORGET, IF END OF LIFE CARE…

- If at the end of life, start anticipatories?

- Stop unnecessary meds

- Get Palliative Care involved? Gold Line?

- DNACPR/RESPECT Forms – discuss with patient/relatives and complete.

- Keep care home staff in the loop.

Dementia at a Glance

Basically…

increasing difficulties with tasks and activities

that require concentration & planning

Common features

- memory loss

- periods of mental confusion; low attention span (e.g. repeatedly reminding of time etc);wandering during the night

- changes in personality

- changes in mood (often depression features)

Additional features

- slow and unsteady gait

- stroke-like symptoms, such as muscle weakness or paralysis on one side of the body

- visual hallucinations

- urinary incontinence

- Age

- ≥ 60 with cardiovascular disease (CVD), stroke, peripheral vascular disease or diabetes;

- ≥ 50 with learning disabilities

- ≥ 40 with Down’s syndrome;

- Existing Medical Conditions

- Chronic disease – depression, hypothyroidism, HIV

- Long-term neuro conditions which have a neurodegenerative element – Parkinson’s disease, MND, MS

- Learning difficulties (esp Down’s syndrome)

Other Factors

- Social isolation.

- Chronic alcoholism

- Malnutrition

- Smokers

- Good History with specific examples of behaviour – usually from the patient and family or carers.

- Specifically ask about: aggression, agitation, and wandering.

- Consider Home Visit to assess situation at home.

- Review Medication – is any medication that may impair cognitive functioning?

- Mental State Examination. Is there Delirium, Depression, Psychosis? Exclude acute potentially reversible causes of confusion/delerium. 6CIT or MMS

- Physical Examination – full physical including NEURO Ex. Rule out reversible conditions – infections (LRTI/UTI), constipation, thyroid function, diabetes etc

- Must do a 6CIT or MMS

- Bloods: FBC, U&ES, LFTs, HbA1c, calcium, B12, folate, TSH (syphilis serology or HIV screen should only be taken if history suggests risk).

- MSU – exclude infection

- May need ECG/X-rays according to clinical presentation.

See DOWNLOADS section above under “memory assessment tests” for the different tests available.

The Limitations of all memory assessment tests like AMTS, MMS, 6-CIT:

- These tests DO NOT assess the frontal lobe! For example, things like frontal lobe dementia (often in younger people), frontal lobe dysfunctions like Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome.

- So how do you pick up frontal lobe disorders? Answer – from relatives mentioning, or you noticing (if you know the patient well) a “coarsening of personality”. The characteristic coarsening of personality involves things like

- a loss of social, and sometimes sexual, inhibitions

- a tendency to irritability, a facile jocularity, and abusiveness.

- And this leads to…

- family disruption (violence in the home and marital separation);

- an increased rate of accidents at home, work and on the road;

- and increased rates of absenteeism, redundancy, offending and vagrancy.

- Sexual impotence may also develop.

- Sometimes, the syndrome of ‘morbid jealousy’ may emerge.

- May lead to a “Dysexecutive Syndrome” picture.

- In the case of alcohol-related disorders, this is not necessarily related to acute intoxication.

- Stop/reduce medication that may impair cognitive functioning.

- Referral to MEMORY ASSESSEMENT CLINIC. Early diagnosis is emphasised by NICE in order to access resources for patient/carers, planning and medication.

- Confirmation of diagnosis of dementia

- Suitability for medication

- Problematic behavioural/psychological symptoms management

- Safety Risk assessment

- lllSupport for patient/carer

- Review social situation including mobility, carer and/or family support and concerns, including potential for abuse/ neglect

- Once diagnosis CONFIRMED: Provide patient/carers with ADVANCED CARE PLANNING booklet. In clinical system (e.g. Systm One, tick ADVANCED CARE PLAN DECLINED if patient does not wish to engage.

GPs should continue to do primary and secondary prevention – depending on other co-morbidities

The following medications are initiated in secondary care:

Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors such as donepezil, galantamine and rivastigmine are recommended as options for managing mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease

Memantine is recommended as an option for managing Alzheimer’s disease for people with (i) moderate Alzheimer’s disease who are intolerant of or have a contraindication to AChE inhibitors or

(ii) severe Alzheimer’s disease.

- Carer support and assessment- (e.g. Carers Resource, Carer’s Connection Bradford, Alzheimer’s society, Making Space)

- Community care- Home care, day care, respite care.

- Financial– Benefit advice. Refer to below website CAB/DWP.

- Lasting Power of Attorney– property, affairs and personal welfare. Includes healthcare and treatment decisions.

- Advanced decisions – legally binding, can make treatment decisions about their future.

- Making a will – Alzheimer’s society can give details of solicitors with experience in dementia.

- Driving – DVLA & Insurance company must be informed. Their licence may be revoked/ limited, or need regular review.

Hba1c Target: aim for 48mmol/mol (if on diet or single drug not affected by hypoglycaemia ) or <53mmol/mol (if on SU, or more than one medication). Caution: elderly

- Start Oral treatment usually Metformin at diagnosis. Metformin 500mg ideally with evening meal, increasing to 1 gram a week later if they have no side effects.

- Please remember Metformin is very effective, reduces cardiovascular risk, retards weight gain and is not usually associated with hypos – but is contra-indicated if Creatinine > 150 (or eGFR < 40) in CCF or significant hepatic dysfunction.

- Metformin has to be stopped if eGFR fall below 30!

- Metformin MR can be used if they run into problems with GI side effects.

- Don’t forget that on starting hypoglycaemics to complete the prescription exemption form for those patients under 60 years of age.

- If you are starting a sulphonylurea (ideally Glimepiride) – ensure they are counselled and documented about:

- symptoms of hypos

- hypo management

- hypos and driving and remind them about informing their car and travel insurer AND document this in their records. If they hold HGV or PSV license then check with the 6 monthly updated DVLA guidance with respect to them having to inform the DVLA.

- Ensure they have been given a glucometer and a sharps bin, test strips and lancets are added to their repeat prescription

- DISCUSS AKI SICK DAY RULES ADVICE – see hypertension protocol for full advice.

Monitor for adverse effects and drug interactions. The most relevant are:

- Exacerbation of asthma and COPD

- Anorexia and weight loss

- GI ulcer or bleed

- AV node block as a possible cause of collapse

- Potential additive effects with other drugs that share the same side effects (e.g. beta-blockers and bradycardia; SSRIs and anorexia)

Absolute Contraindications | |

All drugs | Where there is hypersensitivity to the active substance or any of the excipients. |

Donepezil | Known sensitivity to piperidine derivatives |

Galantamine | Severe hepatic/renal impairment or those who have both significant renal and hepatic dysfunction. Urinary retention or history of prostatic condition |

Donepezil & galantamine | Patients with rare hereditary problems of galactose intolerance, the Lapp lactase deficiency or glucose-galactose malabsorption |

Rivastigmine | Known hypersensitivity to carbamate derivatives or severe liver impairment |

Memantine | Patients with rare hereditary problems of fructose intolerance should not take oral solution (contains sorbitol). |

Cautions – to be used with caution in the following | ||

AChE | May exacerbate/induce extrapyramidal symptoms • AV node block • People at • Severe asthma increased risk of • Concomitant digoxin or peptic ulcers beta-blocker therapy (those with history • Urinary symptoms (avoid of ulcer disease or use of galantamine) on concomitant NSAIDs |

• Obstructive pulmonary disease or active pulmonary infections • Epilepsy • CVD |

inhibitors | ||

(donepezil, | ||

galantamine, | ||

rivastigmine) | ||

Memantine | • History of convulsions • Patients with recent MI, uncontrolled hypertension or uncompensated congestive heart failure were excluded from the clinical trials and there is limited data for the use in these patients. These patients should be closely supervised.

|

|

| Adverse effects of AChE inhibitors (donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine) and suggested actions | |||

There are two practically important groups of adverse effects: 1. GI – common S/Es include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, anorexia, weight loss 2. Cardiac • heart block (sino-atrial block, AV block) – this is rare but potentially serious and easily missed • bradycardia – if this occurs, carry out an ECG. If symptoms of collapse or dizzy spells and PR interval >200ms, then stop AChE inhibitor | ||||

Adverse effects | Symptoms/signs | Frequency | Suggested actions | |

GI symptoms | Anorexia, nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea | Very common | Generally mild and transient. Can be minimised by taking drug after food. If symptoms persist, reduce dose. If unsuccessful, consider switch to alternative AChE inhibitor. | |

May enhance predisposition to gastric or duodenal ulceration | Uncommon/rare | Discontinue treatment if ulcer develops. Care with those at risk of or with active gastric or duodenal ulcer. Patient should be monitored regularly for symptoms. | ||

Cardiovascular symptoms | Bradycardia | Uncommon/rare | Seek urgent review. Carry out an ECG. If symptoms of collapse or dizzy spells and PR interval >200ms then stop AChE inhibitor. Increased risk with ‘sick sinus syndrome’, sinoatrial or atrioventricular block or those receiving concomitant treatment with digoxin or beta-blockers. In such cases, stop treatment and undertake urgent review. | |

Neurological symptoms | Dizziness, headache, insomnia, somnolence | Very common/ common | Generally mild and transient. If symptoms persist, reduce dose. If unsuccessful, consider switch to alternative AChE inhibitor. | |

Syncope | Common/ uncommon | Reduce dose. If symptoms persist, consider switch to alternative AChE inhibitor. | ||

Extrapyramidal symptoms (including worsening of Parkinson’s disease) | Rare | Reduce dose. If symptoms persist, consider switch to alternative AChE inhibitor | ||

Decreased seizure threshold | Rare | Extreme caution in epilepsy | ||

Skin | Galantamine has been associated with serious skin reactions including Stevens Johnson Syndrome (SJS), acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) and erythema multiforme. | Rare | It is recommended that patients and carers are advised to monitor for skin reactions. In the advent of an apparent skin reaction patients should be advised to stop treatment and seek medical advice | |

General disorders | Asthenia, fatigue | Common | Generally mild and transient. If symptoms persist, reduce dose. If unsuccessful, consider switch to alternative AChE inhibitor. | |

Respiratory symptoms | May cause bronchoconstriction | No data available | Caution in patients with history of asthma or COPD or those with an active pulmonary infection (pneumonia). | |

Psychiatric symptoms | Agitation, confusion and insomnia | Common | Reduce dose. If symptoms persist, consider switch to alternative AChE inhibitor. | |

Adverse effects of memantine and suggested actions | |||

Appears to be well tolerated in practice but it is important to note that it might be easy to miss distressing side effects when it is used exclusively in a population with severe dementia. | |||

Adverse effects | Symptoms/signs | Frequency | Suggested actions |

GI symptoms | Constipation | Common | PRN or regular laxative |

Cardiovascular symptoms | Hypertension | Common | Reduce dose and review BP. Consider discontinuation |

Neurological symptoms | Dizziness, headache, drowsiness | Common | Reduce dose and review symptoms. Consider discontinuation |

Respiratory symptoms | Dyspnoea | Common | Reduce dose and review symptoms. Consider discontinuation |

Drug Interactions | |

All AChE inhibitors | • May interact (antagonism of effects) with medicines that have anticholinergic activity e.g. oxybutynin, antipsychotics and tricyclics. • Potential for synergistic activity with medicines such as succinylcholine (suxamethonium) and other neuromuscular blocking agents, cholinergic agonists or beta-blocking agents that have effects on cardiac conduction. • Potential for additive effects with other drugs that share the same side effects e.g. beta blockers and bradycardia, SSRIs and anorexia) |

Donepezil and galantamine | Metabolised via CYP3A4 and CYP2D6 pathways in the liver. Inhibitors of these pathways (e.g. erythromycin, clarithromycin, ketoconazole, fluvoxamine, fluoxetine, paroxetine) may increase drug levels and patients may experience increased side effects. A dose reduction may be required. Enzyme inducers (e.g. rifampicin, phenytoin, carbamazepine and alcohol) may reduce levels so care should be taken with concurrent prescribing. |

1. Compliance – is the medication being taken properly? | |||

2. Physical Health Monitoring | |||

Weight | If weight loss has started or accelerated after starting AChE inhibitor medication, this may be the cause | ||

Pulse/BP | If <60, carry out an ECG. If PR interval > 200ms, stop drug or discuss with mental health specialist | ||

Overall tolerance to medication | GI symptoms – anorexia, nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea Neurological symptoms – headaches, dizziness, drowsiness, syncope | ||

3. Impact on global functioning | |||

Functional and behavioural assessment is best made via a discussion with the patient and carer (it might be important to see the carer alone to elicit behavioural problems). | |||

Functional assessment | Impact on daily living. Is there declining function? Risk of falls, injuries. Nutritional status. Safety at home? | Review whether referral to Social Services (HCS) is required for declining function OT/physio/falls assessment | |

Carer Impact | Does the carer value the effect of the medication? | It is important to take into account the impact of the medication to the carer. | |

Behavioural assessment | New behavioural problems? Is the patient displaying behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD)? Ability to cope? | Review whether standard or urgent referral to SMHTOP via SPA is needed for new behavioural problems | |

4. Cognitive Assessment | |||

• Some patients are distressed by repeated use of formal cognitive scoring tests. Therefore it is not always necessary to repeatedly use a formal scale to measure cognition as this can also be assessed via patient and carer interview. Use of formal cognitive scales is not mandatory. It is also important to consider the global functioning of the patient by discussion with the carer/relatives. | |||

• However in some cases a formal test can help find severe dementia and highlight that ongoing benefit of treatment is unlikely. An unexpectedly large change in a test score might prompt a conversation about other problems that need management – e.g. increased care package. • When the use of a formal cognitive scoring test is appropriate (e.g. when there has been a significant deterioration in the global functioning), consider using either of the following open access primary care validated scales – 6CIT (six item cognitive impairment test) or GPCOG (the General Practitioner assessment of Cognition). | |||

| 5. Is the medication still of overall benefit?

How to Stop

| ||

6. REMEMBER TO REVIEW OTHER LONG-TERM ILLNESSES

- Difference of opinion between primary care team and carer about stopping medication

- Consideration of switch to memantine in severe dementia

- Uncertainty about side effects or benefits

- Behavioural problems that would require the community team whether or not the patient is taking anti- dementia medication

Stroke at a Glance

See under Cardiovascular Medicine

Prescribing & De-Prescribing for the Elderly

Tell the patient

When you are unwell with any of the following…

- Vomiting or Diarrhoea (unless only minor and mild)

- Fevers, sweats and shaking (unless only minor and mild) – this can often happen with common cold/flu, chest infections, water infections

Then

- STOP taking the medicines I have written down for you

- Restart these when you are well (after 24-48 hours of eating and drinking normally)

- If you are in any doubt, contact the pharmacist, doctor, nurse or call 111.

Also

- Take some rest

- Drink plenty of sugar-free fluids. Aim to drink at least three litres (five pints) a day, UNLESS YOU HAVE HEART FAILURE – in which case ask your Heart Failure nurse or GP or ring 111 (you may need to stick to around 1.5-2 litres). If you have Heart Failure, weigh yourself every day. If you suddenly gain more than 2Kg in 3 days, contact the emergency doctor or call 111.

- Try to keep to your normal meal pattern, but if you are unable to, for any reason, you can replace some or all of your meals with snacks and/or drinks that contain carbohydrate such as yoghurt, milk and other milky drinks, fruit juice or sugary drinks such as Lucozade, ordinary cola or lemonade. You may find it useful to let fizzy drinks go flat to help keep them down

- Avoid too much caffeine as this could make you dehydrated.

- Take painkillers in the recommended doses as necessary.

- Contact your GP to see if treatment with antibiotics is necessary.

- If you are vomiting uncontrollably, contact your GP or call 111

- Keep taking your insulin or diabetes medications even if you are not eating. HOWEVER, stop metformin and blood pressure medication if you are dehydrated.

- Test your blood four or more times a day and night (ie at least eight times in a 24-hour period) and write the results down. If you are not well enough to do this, ask someone to do it for you.

- Test your urine four or more times a day and night (ie at least eight times in a 24-hour period) and write the results down. If you are not well enough to do this, ask someone to do it for you.

- Testing for ketones

- When diabetes is out of control as a result of severe sickness, it can lead to a condition called diabetic ketoacidosis or diabetic coma if you have Type 1 diabetes. The body produces high levels of ketone bodies causing too much acidity in the blood.

- If you have Type 1 diabetes and your blood glucose level is 15 mmol/l or more or you have two per cent or more glucose in your urine, you will also need to test your urine or blood for ketones. They are a sign that your diabetes is seriously out of control. Ketones are especially likely when you are vomiting and can very quickly make you feel even worse. If a ketone test is positive, contact your GP or diabetes care team immediately.

Medicines to STOP on sick days (mnemonic SADMAN)

- SGLT-2 inhibitors: medicine names ending in “flozins” like canagliflozin, empagliflozin, dapagliflozin

- ACE inhibitors: medicine names ending in “pril” like ramipril, lisonopril, enalapril, captopril, perindopril

- Diuretics: e.g. medicine names ending in “ide” like furosemide, bendroflumethiazide, bumetanide

- Metformin (which is a medicine for diabetes)

- ARBs: medicine names ending in “sartan” like losartan, candesartan, valsartan, irbesartan

- NSAIDs: anti-inflammatory pain killers like ibuprofen, diclofenac, naproxen, ketoprofen

- People aged 65 and older have the highest risk of falling, with 30% of people older than 65 and 50% of people older than 80 falling at least once a year. So, it’s important to reduce polypharmacy and avoid unnecessary medicines.

- The two groups of drugs that have the highest propensity to cause falls are those acting on the brain and those acting on the heart and circulation.

- There is good evidence that stopping psychotropic drugs (including opioid analgesics) can reduce falls.

- Taking a psychotropic medication approximately doubles the risk of falls:

- More from these wonderful websites: STOPPFall and Care Homes Guidance: PRESCQIPP

- Remember the NNTs behind the evidence base – often these are extrapolated to older age groups without any specific evidence of benefit.

- NNTs tell us that most medicines do not produce optimal effects in most people, but all may experience adverse effects.

- Recommend focus on person-centred outcomes to assess benefit. The benefit/risk ratio will change as we age.

- Review repeat medications – have a system for repeat medications in place.

- A drug may be necessary but also can be a potential risk. For example, remember that with age there is often declining renal function and changing pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in older people.

- Clarity about the indication and the intended outcome for each medicine is needed, especially now we have a wider range of prescribing colleagues.

- If a patient is non concordant with their prescribed medication, maybe they are giving you a valuable hint. Iatrogenic illness causes significant morbidity and mortality. One question required, is this treatment essential? If no… stop it’. Evidence tells us that 30 – 50% of people do not take medicines as prescribed.

- Nitrofurantoin: long-term (greater than six months) use of nitrofurantoin is associated with pulmonary toxicity. CARM have received over 60 reports of serious pulmonary reactions following the use of nitrofurantoin.

- MEDICATION REVIEWS

- It is always worth being alert to the triggers that signal the need for consideration of a timely medication review and potential deprescribing; these include:

- request for a dosette box

- a fall

- increasing confusion/drowsiness

- constipation

- admission to a care home due to increasing frailty etc

- It is always worth being alert to the triggers that signal the need for consideration of a timely medication review and potential deprescribing; these include:

Fall-risk assessment:

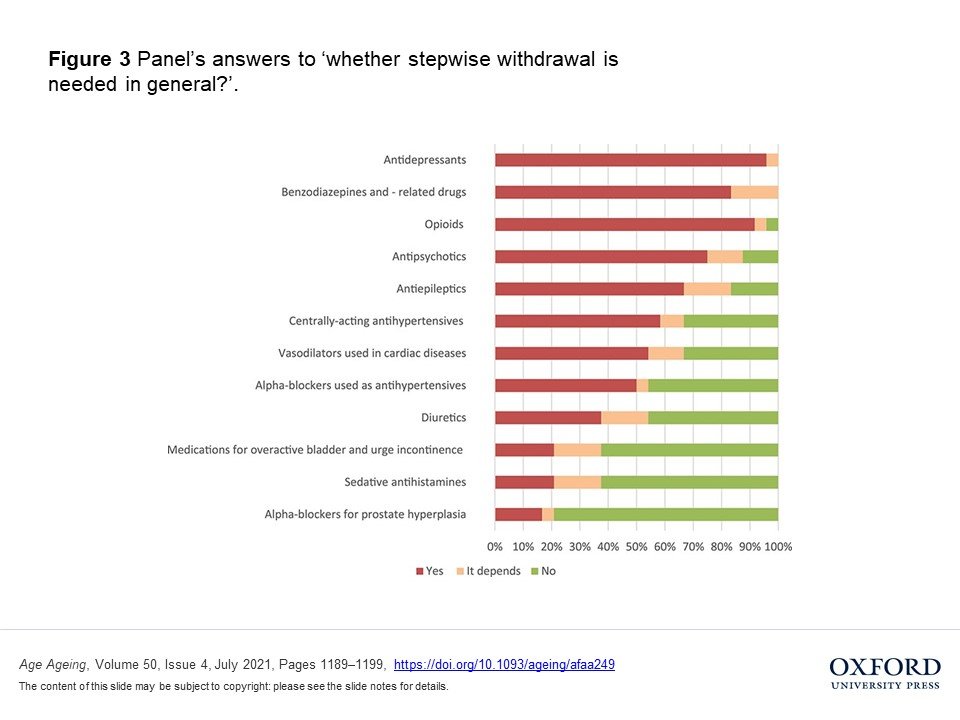

In which cases to consider withdrawal?aIs stepwise withdrawal needed?b Monitoring after deprescribingc Always -If no indication for prescribing-If safer alternative available -Fall incidence and change in symptoms e.g. OH, blurred vision, dizziness-Organise follow-ups on individual basis Benzodiazepines (BZD) and BZD-related drugs -If daytime sedation, cognitive impairment, or psychomotor impairments

-In case of both indications: sleep and anxiety disorderIn general needed -Monitor: anxiety, insomnia, agitation

-Consider monitoring: delirium, seizures, confusionAntipsychotics -If extrapyramidal or cardiac side effects, sedation, signs of sedation, dizziness, or blurred vision

-If given for BPSD or sleep disorder, possibly if given for bipolar disorderIn general needed -Monitor: recurrence of symptoms (psychosis, aggression, agitation, delusion, hallucination)

-Consider monitoring: insomniaOpioids -If slow reactions, impaired balance, or sedative symptoms

-If given for chronic pain, and possibly if given for acute painIn general needed -Monitor: recurrence of pain

-Consider monitoring: musculoskeletal symptoms, restlessness, gastrointestinal symptoms, anxiety, insomnia, diaphoresis, anger, chillsAntidepressants -If hyponatremia, OH, dizziness, sedative symptoms, or tachycardia/arrhythmia

-If given for depression but depended on symptom-free time and history of symptoms or given for sleep disorder, and possibly if given for neuropathic pain or anxiety disorderIn general needed -Monitor: recurrence of depression, anxiety, irritability and insomnia

-Consider monitoring: headache, malaise, gastrointestinal symptomsAntiepileptics -If ataxia, somnolence, impaired balance, or possibly in case of dizziness

-If given for anxiety disorder or neuropathic painConsider -Monitor: recurrence of seizures

-Consider monitoring: anxiety, restlessness, insomnia, headacheDiuretics -If OH, hypotension, or electrolyte disturbance and possibly if urinary incontinence

-possibly if given for hypertensionConsider -Monitor: heart failure, hypertension, signs of fluid retention Alpha-blockers (AB) used as antihypertensives -If hypotension, OH, or dizziness Consider -Monitor: hypertension

-Consider monitoring: palpitations, headacheAB for prostate hyperplasia -If hypotension, OH, or dizziness In general not needed -Monitor: return of symptoms Centrally-acting antihypertensives -If hypotension, OH, or sedative symptoms Consider -Monitor: hypertension Sedative antihistamines -If confusion, drowsiness, dizziness, or blurred vision

-In case of all indications: hypnotic/sedative, chronic itch, allergic symptomsConsider -Monitor: return of symptoms

-Consider monitoring: insomnia, anxietyVasodilators used in cardiac diseases -If hypotension, OH, or dizziness Consider -Monitor: symptoms of Angina Pectoris Overactive bladder and incontinence medications -If dizziness, confusion, blurred vision, drowsiness, or increased QT-interval Consider -Monitor: return of symptoms aThis column includes answer categories that were chosen by more than 70% of the experts. In addition, after word ‘possibly’ are indicated the categories that were selected by 30–70% of the experts.

b‘In general needed’ indicates that >70% of experts chose categories of yes or depending. ‘Consider’ indicates that 30–70% of experts chose categories of yes or depending. ‘In general not needed’ indicates that <30% of experts chose categories of yes or depending.

c‘Monitor’ refers to >70% of the experts selecting these symptoms. ‘Consider monitoring’ refers to 30–70% of the experts selecting these symptoms. BPSD, behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia; OH, orthostatic hypotension.

STOPPFrrail is a list of potentially inappropriate prescribing indicators designed to assist physicians with deprescribing decisions. It is intended for older people with limited life expectancy for whom the goal of care is to optimise quality of life and minimise the risk of drug-related morbidity. Goals of care should be clearly defined, and, where possible, medication changes should be discussed and agreed with patient and/or family.

Appropriate candidates for STOPPFrail-guided deprescribing typically meet ALL of the following criteria:

1. Activities of daily living dependency (i.e. assistance with dressing, washing, transferring, walking) and/or severe chronic disease and/or terminal illness. 2. Severe irreversible frailty, i.e. high risk of acute medical complications and clinical deterioration. 3. Physician overseeing care of patient would not be surprised if the patient died in the next 12 months.Section A: General • Any drug that the patient persistently fails to take or tolerate despite adequate education and consideration of all appropriate formulations.

• Any drug without a clear clinical indication.

• Any drug for symptoms which have now resolved (e.g. pain, nausea, vertigo, pruritus)Section B: Cardiology system • Lipid-lowering therapies (statins, ezetimibe, bile acid sequestrants, fibrates, nicotinic acid, lomitapide and acipimox).

• Antihypertensive therapies: Carefully reduce or discontinue these drugs in patients with systolic blood pressure (SBP) persistently <130 mmHg. An appropriate SBP target in frail older people is 130–160 mmHg. Before stopping, consider whether the drug is treating additional conditions (e.g. beta-blocker for rate control in atrial fibrillation, diuretics for symptomatic heart failure).

• Anti-anginal therapy (specifically nitrates, nicorandil, ranolazine): None of these anti-anginal drugs have been proven to reduce cardiovascular mortality or the rate of myocardial infarction. Aim to carefully reduce and discontinue these drugs in patients who have had no reported anginal symptoms in the previous 12 months AND who have no proven or objective evidence of coronary artery disease.Section C: Coagulation system • Anti-platelets: No evidence of benefit for primary (as distinct from secondary) cardiovascular prevention.

• Aspirin for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: Aspirin has little or no role for stroke prevention in frail older people who are not candidates for anticoagulation therapy and may significantly increase bleeding risk.Section D: Central nervous system • Neuroleptic antipsychotics in patients with dementia: Aim to reduce dose and discontinue these drugs in patients taking them for longer than 12 weeks if there are no current clinical features of behavioural and psychiatric symptoms of dementia (BPSD).

• Memantine: Discontinue and monitor in patients with moderate to severe dementia, unless memantine has clearly improved BPSD.Section E: Gastrointestinal system • Proton pump Inhibitors: Reduce dose of proton pump inhibitors when used at full therapeutic dose ≥8 weeks, unless persistent dyspeptic symptoms at lower maintenance dose.

• H2 receptor antagonist: Reduce dose of H2 receptor antagonists when used at full therapeutic dose for ≥8 weeks, unless persistent dyspeptic symptoms at lower maintenance dose.Section F: Respiratory system • Theophylline and aminophylline: These drugs have a narrow therapeutic index, have doubtful therapeutic benefit and require monitoring of serum levels and interact with other commonly prescribed drugs putting patients at an increased risk of ADEs.

• Leukotriene antagonists (montelukast, zafirlukast): These drugs have no proven role in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; they are indicated only in asthma.Section G: Musculoskeletal system • Calcium supplements: Unlikely to be of any benefit in short-term unless proven, symptomatic hypocalcaemia.

• Vitamin D (ergocalciferol and colecalciferol): Lack of clear evidence to support the use of vitamin D to prevent falls and fractures, cardiovascular events or cancers.

• Anti-resorptive/bone anabolic drugs for osteoporosis (bisphosphonates, strontium, teriparatide, denosumab)

• Long-term oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: Increased risk of side effects (e.g. peptic ulcer disease, bleeding, worsening heart failure) when taken regularly for ≥2 months.

• Long-term oral corticosteroids: Increased risk of major side effects (e.g. fragility fractures, proximal myopathy, peptic ulcer disease) when taken regularly for ≥2 months. Consider careful dose reduction and discontinuation.Section H: Urogenital system • Drugs for benign prostatic hyperplasia (5-alpha reductase inhibitors and alpha-blockers) in catheterised male patients: No benefit with long-term bladder catheterisation.

• Drugs for overactive bladder (muscarinic antagonists and mirabegron): No benefit in patients with persistent, irreversible urinary incontinence unless clear history of painful detrusor hyperactivity.Section I: Endocrine system • Anti-diabetic drugs: De-intensify therapy. Avoid HbA1c targets (HbA1C <7.5% [58 mmol/mol] associated with net harm in this population). The goal of care is to minimise symptoms related to hyperglycaemia (e.g. excessive thirst, polyuria). Section J: Miscellaneous • Multivitamin combination supplements: Discontinue when prescribed for prophylaxis rather than treatment of hypovitaminosis.

• Folic acid: Discontinue when treatment course is completed. The usual treatment duration is 1–4 months unless malabsorption, malnutrition or concomitant methotrexate use.

• Nutritional supplements: Discontinue when prescribed for prophylaxis rather than treatment of malnutrition.Disclaimer (STOPPFrail): While every effort has been made to ensure that the potentially inappropriate deprescribing criteria listed in STOPPFrail are accurate and evidence-based, it is emphasised that the final decision to deprescribe any drug referred to in these criteria rests entirely with the prescriber. It is also to be noted that the evidence base underlying certain criteria in STOPPFrail may change after the time of publication of these criteria. Therefore, it is advisable that deprescribing decisions should take account of current published evidence in support of or against the use of drugs or drug classes described in STOPPFrail.

Stepwise withdrawal is needed in the following…

- KIK Medication Withdrawal Decision Tree

- STOPFALL – prescribing & de-prescribing in the elderly to prevent falls

- STOPPFrail version 2 – see above

- MEDICHEC tool – Medichec helps to identify medications that might have a negative effect on cognitive function and/or other adverse effects in older people. Medichec analyses medication that may have anticholinergic effects, defines the extent of the effect and the cumulative implications of multiple drugs. Medications with a high anticholinergic burden can increase the risk of cognitive impairment in older people and research evidence indicates associations with an increased risk of developing dementia and early death. Medichec also identifies medications that are reported to cause dizziness and drowsiness and ranks them according to the frequency of reported adverse effects. Dizziness and drowsiness can add to cognitive impairment and confusion in older people and can increase the risk of falls.

- NHS Scotland: 7 Steps Approach to Medication Review & Polypharmacy

- Canadian deprescribing resources

- Difference of opinion between primary care team and carer about stopping medication

- Consideration of switch to memantine in severe dementia

- Uncertainty about side effects or benefits

- Behavioural problems that would require the community team whether or not the patient is taking anti- dementia medication